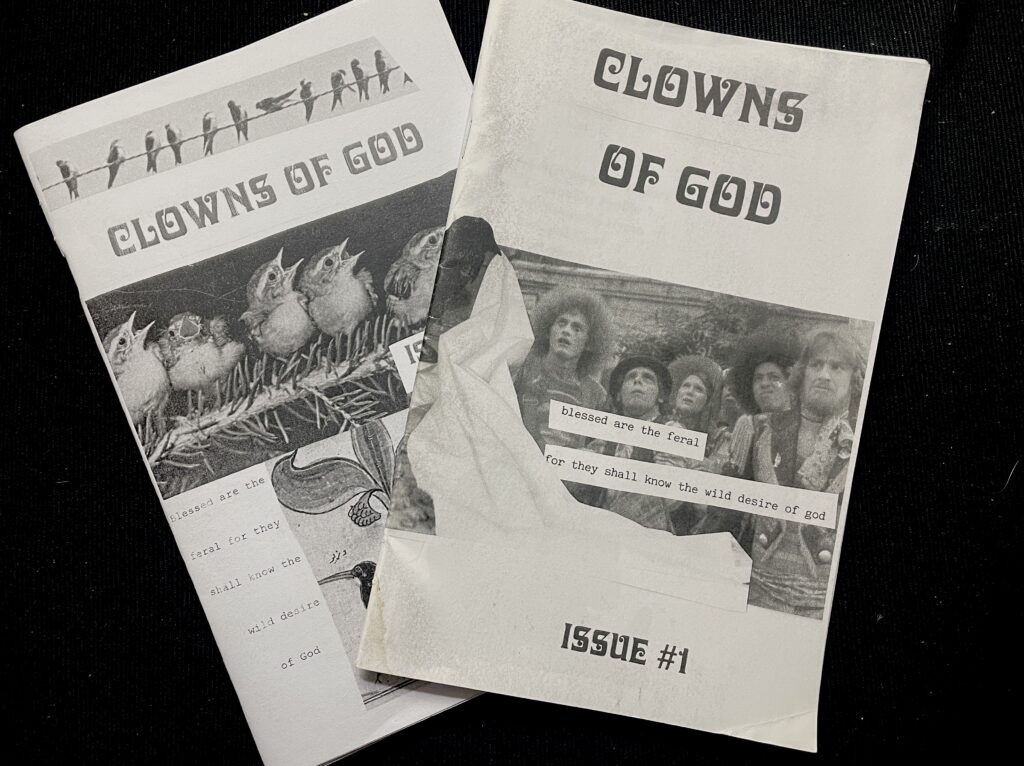

The good folks at the Clowns of God ‘zine recently asked me to be interviewed for their upcoming Advent issue.

Here’s what I said:

Tell us about yourself! What do you spend your time doing?

I’m Rob Shearer – I guess I’m a bit of a walking contradiction of being a proudly nonviolent anti-fascist anarchist and activist AND an orthodox, Trinitarian, creedal, Jesus-loving Christian, a minister in the United Church of Canada AND a queer person. I’m also a full-time church bureaucrat who supports new communities of faith in my day job.

Most importantly, I’m a single parent of these two amazing teenagers who give me a reason to get up in the morning in these bleak days.

I’m a very amateur musician and poet and I love a good bleak mystery book or show. I also scour thrift stores to collect used vinyl records – I’m mostly looking for African-American gospel these days.

I co-founded a now decade-old community based on monastic principles – Emmaus Community – where we take vows of prayer, presence and simplicity. And out of that has also flowed in the formation of a small ragamuffin worshipping community – AbbeyChurch. Those give me a good foundation of prayer and worship and sacrament in community – because I kind of suck at spiritual practice on my own.

I’m passionate about the idea of intentional community and a local shared common life – going from temple to table daily – re-imagining land and space and stuff outside of ownership can be one way the world can be reshaped for the common good.

What are you excited about these days?

What excites me? Hmm, I hate to say it, but I think it’s the apocalypse that excites me most these days (laughs).

This is an Advent issue, right? This time of year the church lectionary takes us through a lot of apocalyptic texts – and apocalypse means revealing or uncovering, right? I think the old heresies of Christian nationalism, colonialism, fascism as well as neo-liberalism are being revealed for what they are – and both the capitalist and liberal projects are coming to an end. I find a lot of hope in that, as awful and painful as it all is as things fall apart.

I think if I didn’t have some kind of eschatological hope in it all, that Jesus’ reign is going to break through, and is breaking through – and already has… like Jesus did that first time in the incarnation some 2000 years ago, If I didn’t have that cosmic hope, I’d be utterly despondent.

I’m also excited about ‘revival’. I think there’s something buzzing under the surface right now among younger people – Gen-Z types and others who have had enough of the bullshit of modernity – both its conservative fundamentalist and liberal-progressive fundamentalist poles – both of which have left us longing for something more. Longing for praise and proclamation that Jesus is Lord – which flows into works of mercy.

As a United Church minister, I have Methodism in my DNA – and I think we need an old fashioned Holy Ghost revival to shake our foundations – and I think it’s happening. I think it’s coming from the edges; in the church it’s from diasporic and migrant communities, from younger from BIPOC Christians – and from Jesus-loving queer folk. It’s powerful. It could be easily coopted – but I’m hopeful.

Talk to us about your theology. How does it inform the work you do?

In my late teens, I deconstructed myself out of my Pentecostal-holiness tradition of my childhood because I looked into how that tradition did gender and ecology and culture – and ended up journeying through the flip-side of Christian holiness – anarchist activism – and then, after a very brief and unsatisfying dip into liberal or progressive theologies, I got into liberation kinds of theologies.

However, there was something about the primal ‘first love’ call of Jesus, that Holy Spirit power I experienced at a camp meeting altar call that led me, reluctantly, into ministry, that was and is deep in my bones. Liberal church just didn’t cut it. Activism burned me out several times. And Jesus wouldn’t let me go.

I got into contemplative prayer – Ignatian spirituality, Taize, silent prayer – as well as liturgical and sacramental traditions of the Church. And long bike rides and hikes. God in creation.

At some point I realised that most of my ’social justice’ heroes in the church are also very devout, orthodox Christians.

I was Roman Catholic for five years before being ordained an Anglican priest and then being received into the United Church. This is either reckless infidelity to one tradition – or just an ability to see God in so many places, so many people, so many ways. Probably both.

Praise music and the spirituals of the African-American gospel and spiritual tradition have been a huge part of my reconstruction and draw back to my roots.

Looking back, I’ve learned to love all of these disparate yet somehow cohesive parts of the Christian tradition – so I guess I’d say my theology is liberationist, charismatic, contemplative, orthodox, radical and sacramental.

In spite of all the terror of the church – it’s hurt me so bloody much – and others so much more than me – I’ve somehow fallen in love with all of these and other elements of it. With that, I guess I’d also say I have a hermeneutic of suspicion towards the institution – be it conservative or liberal – flip sides of the same coin that they are – and that sometimes gets me in trouble. But I think I’m in good company in that.

At the end of the day, if I have an operative theology, I’d like it to be one centred on love and grace. I have a bit of a low anthropology too. And in that, I know that I been saved by grace – for God knows this broken sinner and beautiful soul made in the very image of God needs it. That really hasn’t changed much in all these years.

But it has led me to a hopeful universalism. That ALL shall be saved.

Universalism?

Ya, like when St. Paul underlines the renewal of all things, he means it. When scripture says that nothing can separate us from God’s love, it means it. I don’t actually know if this is actually true, but it’s my deep hope – and the best way I can even begin to understand a God of love, mercy and grace. This re-shapes my call as a minister, preaching, how evangelism works, praise and worship, how I view the ‘other’, the purpose of the Church – and so much more.

I have to admit that though I’m not totally sure I’m into purgatory as a concept or place, but I do think that notion of purgation of what we’ve done wrong is appealing. Be that in life or after death.

In the United Church creed, we talk about Jesus as ‘our judge and our hope’. I do think we need to account for the things we do – ‘cause we do shitty things – sometimes really awful things. I’m not about universal love without consequence. Grace isn’t cheap, if I can invoke that cliche. I love the idea that there’s some way of working that out – of deep accountability.

But that in the end, the power of Jesus’ incarnation, the cross and resurrection redeems and embraces all things, all people, all creation. It’s so beautiful.

You have a long history engaging in radical Christian hospitality. Do you have any lessons that you can share with us?

Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker have been my best ‘western’ teachers around hospitality. And my single mama and dad too who took in my couch surfing friends and others in need.

I say western or northern, because anytime I’ve travelled outside of contexts of privilege and comfort, such as my own suburban childhood and my own current existence as pretty middle class, I’ve experienced an even deeper, more natural kind of hospitality. In Latin America, in First Nations Contexts, in Africa, in poorer communities here in North America – in migrant households I’ve lived in – it’s like it’s natural, this hospitality thing. I’ve been honoured to be the guest so many times.

Having said that, I love the Catholic Worker Movement for its specific faith-based embodiment of hospitality.

When I lived in a house of hospitality, in addition to taking in folks in so many predicaments, we had a kidnapping of one of our founders in Iraq, and someone who we had to ask to leave who came back and took his life on our front porch. ‘Love in practice is a harsh and dangerous thing compared to love in dreams’, Dorothy Day used to say, quoting Dostoevsky. It’s like living on the tip of an iceberg, one of our co-founders used to say.

I think if there’s one thing Dorothy and that movement didn’t teach us much about it was about boundaries, about prioritising our commitments – as, say, a parent or spouse – about how to heal when our broken attempts at making space bite us. She also didn’t say much about how power gets played out in the ‘host and guest’ paradigm of hospitality. And I’ve been working that stuff out as a parent, a minister, an activist since my time in the worker.

You know, Dorothy said that the goal was that each Christian household would live this way [of hospitality], always being ready to take in the stranger. I think that’s what I’ve learned too. Something like a ‘house of hospitality’ is an amazing witness, because it’s so radical and communal and wild. I wouldn’t trade in that experience for anything. It taught me everything about faith and relying on God. But it can also make the rest of us feel like the work has been done.

These days I’m most deeply moved by small, often unsung acts of hospitality and presence that I see folks doing all around me.

Anything else you’d like to tell us?

The world is really really awful right now. Many days I feel like everything I’ve worked for for 40 plus years is unravelling – in ecology, in geo-politics, even in the church. It’s just mean, as one of my Emmaus siblings says. But. even still, I’m hopeful, in spite of the sheer force of violence and other forms of evil all around. Again, that’s what Advent is about – the impossible and scandalous hope – love amidst the rubble. Grace and love will win.

That’s my last word.